Psychosomatic Disorders in Teenagers: What Teen Mind Body Disorders Are

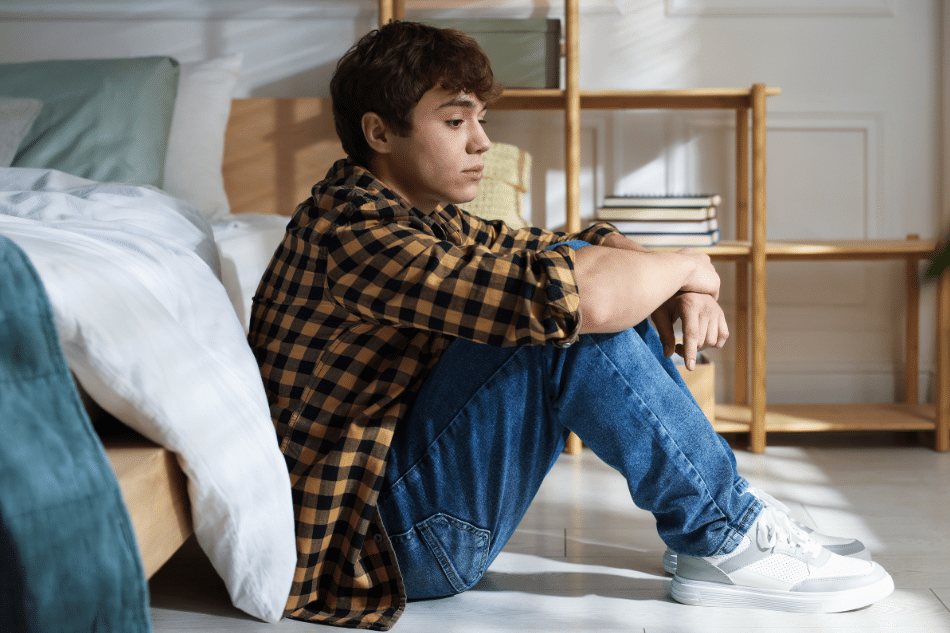

It might not always feel easy to know when to trust your teen’s complaints. One evening, they may be trying to convince you that they don’t have to do a math assignment because it’s “National No Homework Night.” And the next morning, they might wake up with another stomachache that conveniently appears minutes before school. Moments like these can make it natural to question whether they’re avoiding responsibilities or exaggerating how they feel.

But what happens when physical complaints keep coming, and every doctor visit ends with normal results? You know there’s something not quite right, yet, on paper, there’s nothing technically wrong. In these types of cases, you may be dealing with psychosomatic disorders.

Dealing with persistent physical issues can be distressing for both teens and parents – especially when there’s a lack of concrete answers. A mental health professional can help you get to the root causes and find relief. This article also works as a useful guide for understanding psychosomatic disorders in teenagers, as it explores:

- The difference between somatic and psychosomatic disorders

- Different types of psychosomatic disorders

- Why psychosomatic disorders can be hard to diagnose

- How Mission Prep can help

The Difference Between a Somatic Disorder and a Psychosomatic Disorder

At first glance, somatic and psychosomatic disorders can look almost identical, with both involving a mix of physical symptoms and psychological factors. Without understanding how each works, it’s easy to confuse them and miss what’s actually going on.

To help you better understand these differences, we break down the symptoms of each in the following sections.

Somatic Symptom Disorders

A somatic symptom disorder (SSD) occurs when a person becomes extremely focused on physical symptoms, such as pain or fatigue.1 To others, these symptoms may look minor, but the distress they cause and the way they interfere with daily life is far greater than what you’d expect from the symptom itself.

Some examples of how SSDs might present in teens include:

- Persistent headaches with no obvious cause

- Ongoing stomach pain that interferes with daily life

- Pain in the limbs that limits walking or exercise

- Fatigue so overwhelming that it keeps a young person in bed even when no illness is found

- Excessive anxiety about the meaning of physical symptoms

- Difficulty focusing on anything but symptoms

- Increased monitoring of the body, like checking for lumps, pain, or changes throughout the day

As we can see here with SSDs, the worry and attention around symptoms tend to amplify their effect. The physical symptoms are real (and perhaps mild), but the focus on them makes life feel dominated by the illness.

Psychosomatic Disorders

A psychosomatic disorder is when stress or emotional strain creates physical symptoms, but it’s key to distinguish that these aren’t “fake.” The symptoms are real, but the root cause is tied to emotional distress rather than a medical condition that shows up on tests.2

To better understand psychosomatic disorders, it can help to imagine the body carrying a weight the mind can’t manage on its own. When stress builds, the systems that usually keep the body steady, like hormones and the immune response, begin to lose balance.3 This imbalance can create physical symptoms that don’t have a straightforward medical explanation.

In teenagers, a psychosomatic disorder can look like:

- Persistent headaches

- Stomach issues that keep flaring up despite normal tests

- Trouble breathing during stressful times

For parents, these symptoms can be deeply confusing: every medical test comes back fine, yet the problems keep appearing. This is the difficult space a psychosomatic disorder can create – symptoms are genuine, but the cause isn’t something you can easily find on a chart.

So, to put the difference between somatic and psychosomatic disorders simply…

- Psychosomatic disorders occur when stress or emotional strain pushes the body into creating physical symptoms.

- SSDs are when physical symptoms are present, but the distress and focus around them become so strong that daily life is disrupted.

Are There Different Types of Psychosomatic Disorders?

The DSM-5 (the manual professionals use to diagnose mental health conditions) doesn’t have a neat box labelled “psychosomatic disorder,” and that can feel confusing. Part of the reason for this is that earlier versions of the manual tried to pin things down by claiming physical symptoms had to be “medically unexplained.” However, this avenue turned out to be a dead end. This is because many conditions that look unexplained at first can later have partial explanations. Therefore, ruling people out on the basis of symptoms being “unexplained” meant real suffering was sometimes brushed aside.4

Another reason is that “psychosomatic disorder” is still a very broad term. It’s used in medicine, psychology, and everyday conversation, but not always in the same way. This makes it hard to pin down into one official diagnostic label.5

But none of this information means that psychosomatic disorders aren’t recognized; they are, but usually under other names and categories. Some of them are more widely talked about than others, and it’s these better-known conditions we’ll look at next.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Irritable bowel syndrome is usually described as a problem with the digestive system, but the story isn’t quite that simple. Many people with IBS notice that their symptoms worsen when they’re under pressure, and research has shown this isn’t just a coincidence. Stress plays a direct role in how the gut behaves, which is why IBS is often seen as a condition that involves both the bowels and the mind.6

For example, when stress builds up, the gut becomes more sensitive to pain signals, and ordinary digestion can feel uncomfortable.6 The speed of movement through the intestines may also change, and other changes in the body can add to the problem.6

For teenagers, IBS symptoms can include:

- Constipation or sudden diarrhoea

- Stomach pain that flares during stressful times

- A feeling of bloating or pressure after eating

- Episodes of nausea without a clear medical cause

Stress can also alter the way the immune system and nervous system respond in the gut, making flare-ups more likely. Even the balance of bacteria in the intestines can shift as a response to stress, adding another physical layer that fuels symptoms.6

What this interaction creates is a difficult-to-deal-with feedback loop: Stress can make IBS symptoms worse, and dealing with these symptoms typically adds even more stress. For teenagers, this can turn into a cycle of stomach pain, school absences, and anxiety that seems impossible to break. It’s why IBS is sometimes described as “an irritable bowel and an irritable brain” working together.

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is usually thought of as a condition of chronic pain, but like IBS, the story is often more complicated. The pain is real, yet stress and emotional strain can play a big part in how severe the symptoms become.7 In fact, fibromyalgia is often considered to be a condition in which the body and mind work together in ways that aren’t always easy to separate.

One of the strongest theories of why this connection happens is that the nervous system becomes overly sensitive to pain signals.7 Stress and early life experiences can lower the brain’s ability to filter pain, so everyday sensations may feel much more intense.7 Over time, this heightened sensitivity can spread through the body, leaving pain in places that don’t show any injury or clear medical cause.

For teenagers, fibromyalgia may show up as:

- Widespread aching or burning pain across the body

- Sleep that doesn’t feel refreshing, even after a full night

- Problems with concentration and memory, often described as “fibro fog”

- Fatigue that lingers through the day and makes ordinary tasks harder

Because symptoms move between the physical and psychological, fibromyalgia is often seen as partly psychosomatic. It isn’t caused entirely by stress, but stress and emotional health can shape how the condition develops and how difficult it is to live with. Understanding it in this way may help explain why treatment often needs to look at both pain management and ways of easing pressure on the mind.

Skin Conditions

Skin conditions are often explained through allergies or genetics, but research has shown that emotions can quite literally “get into the skin.”8 This doesn’t mean every case of eczema or psoriasis is psychosomatic, but stress and emotional distress are linked to flare-ups that don’t always match what doctors find in tests.

Studies demonstrate how the skin and the nervous system are closely connected. Therefore, when stress builds, a lot of things can go wrong with the skin, specifically.8 For example, the skin’s natural barrier can weaken, which can increase the likelihood of infections.8 Also, the immune system can become more reactive, which means sensations like itching may intensify, leading to further skin problems 8. For some people, this connection can mean emotional strain and skin flare-ups arrive side by side.

In teenagers, skin conditions that are connected to emotional stress might look like:

- Acne that worsens during times of anxiety or social pressure

- Eczema or psoriasis that flares around stressful events, such as exams

- Itching that feels harder to tolerate when sleep is disrupted by worry

- Avoiding social situations because of embarrassment about visible skin changes

What this link creates, again, is a feedback cycle: Stress and difficult emotions can make the skin worse, and worsening skin may increase stress. For young people, this feedback loop can be especially tough, fueling both the physical symptoms and the emotional weight that comes with them. It’s another clear example of how conditions that seem like “just the body” often involve the mind as well.

Notable Mentions

Aside from the conditions mentioned, you may also have heard of psychosomatic factors being mentioned in the diagnosis of:

- Sleep disorders

- Obesity

- Seizures

- Inflammatory disorders (like arthritis)

- Tension-type headaches

- Heart disease

- Diabetes

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

These links don’t mean the conditions are caused entirely by the mind, but they may highlight how often psychological and physical health overlap.

Why Psychosomatic Disorders Are So Hard to Diagnose

Psychosomatic disorders are difficult to recognize because they sit in a space that medicine alone often struggles to manage. The symptoms are real and physical, but they’re also tied up with psychological factors. Therefore, when a person seeks help, they often get pulled in two directions at once.9

The typical diagnostic process for IBS is a prime example of this.

On the outside, symptoms like stomach pain, constipation, diarrhea, or stomach pains can look like a straightforward bowel issue. So, of course, if a person experiences these symptoms, the obvious first stop is booking an appointment with a gastroenterologist. The gastroenterologist runs tests to check for inflammation and, perhaps, prescribe medication or suggest changes in diet.

But what happens if this treatment route doesn’t work? In this case, the gastroenterologist will most likely advise the patient to see a mental health professional. They’re not palming off the patient or being lazy in their diagnosis; they’re simply aware that some IBS issues can be psychosomatic.

The mental health professional can approach the issue from a different angle, focusing on how stress and emotional strain can drive gut symptoms. But, of course, they don’t have the expertise and knowledge of the bowel processes that can keep physical symptoms alive.

So now, what we have is a patient trapped in a back-and-forth. The gastroenterologist can’t fully explain the symptoms through biology alone, while the mental health professional can’t account for the physical processes that refuse to settle. Both are right within their own field, but the disorder itself demands more than either side can provide in isolation. Therefore, a disorder like IBS can’t be separated into “only body” or “only mind.” This overlap is why it – and so many other conditions – can be so difficult to diagnose.

Why Psychosomatic Disorders Are So Difficult to Untangle in Teens

If you’re a parent, it can be confusing to work out whether your teen is dealing with a psychosomatic disorder or something closer to a somatic one. The difference isn’t always obvious, and young people often struggle to explain exactly what they’re feeling. What an adult might describe as a clear set of symptoms can come out as vague complaints in a teenager. As a result, getting to the root causes of symptoms can be harder.

This is why many families end up moving from one appointment to another, going through tests that seem to cover every angle but never quite provide answers. Each specialist focuses on a single piece of the puzzle, yet no one puts the whole picture together.

If your teen has shown symptoms of any of the conditions we’ve covered, doctors should always investigate carefully to rule out a physical illness. But when results keep coming back clear and symptoms don’t fade, it may be time to look more closely at the psychological factors that can have such a strong impact.

Mission Prep: Professional Mental Health Support for Physical Issues

When your teen’s struggles seem to sit between the mind and the body, it can be hard to know where to turn. At Mission Prep, we specialise in helping families make sense of these overlaps and support teens whose symptoms may have a psychosomatic element.

Often, these psychosomatic symptoms don’t exist in isolation, and many of the teens we work with are also managing depression, anxiety, trauma, or mood disorders. Each of these conditions can shape how physical symptoms appear.

This is why our programs are built to adapt to your teen’s situation with access to therapies such as CBT, DBT, family therapy, and group support. These therapies can be woven together in ways that address both teen challenges and the needs of your family, giving you practical tools as well as reassurance along the way.

With programs across the US, including both residential and intensive outpatient support, Mission Prep is ready to support your teen and bring relief to your family. Contact us today and take the first step toward lasting change.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2024, July). What Is Somatic Symptom Disorder? Psychiatry.org. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/somatic-symptom-disorder/what-is-somatic-symptom-disorder

- APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2023, November 15). Psychological factors affecting medical condition. Dictionary.apa.org. https://dictionary.apa.org/psychological-factors-affecting-medical-condition

- Chauhan, A., & Jain, C. K. (2023). Psychosomatic Disorder: The Current Implications and Challenges. Cardiovascular & Hematological Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. https://doi.org/10.2174/0118715257265832231009072953

- D’Souza, R. S., & Hooten, W. M. (2023, March 13). Somatic Syndrome Disorders. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532253/

- Rosic, T., Kalra, S., & Samaan, Z. (2016). Somatic symptom disorder, a new DSM-5 diagnosis of an old clinical challenge. BMJ Case Reports, bcr2015212553. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-212553

- Qin, H.-Y., Cheng, C.-W., Tang, X.-D., & Bian, Z.-X. (2014). Impact of Psychological Stress on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(39), 14126–14131. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14126

- Lee, S.-S. (2021). Psychosomatic Approach to Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Concept, Diagnosis and Treatment. Kosin Medical Journal, 36(2), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.7180/kmj.2021.36.2.79

- Gieler, U., Gieler, T., Peters, E. M. J., & Linder, D. (2020). Skin and Psychosomatics – Psychodermatology today. JDDG: Journal Der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 18(11), 1280–1298. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.14328

- Koyama, A., Ohtake, Y., Yasuda, K., Sakai, K., Sakamoto, R., Matsuoka, H., Okumi, H., & Yasuda, T. (2018). Avoiding diagnostic errors in psychosomatic medicine: a case series study. BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-018-0122-3